India produced around 248 million tonnes of milk in 2024–25, up from about 210 million tonnes in 2020–21. In just four years, national milk output has risen by roughly 18%, reinforcing India’s position as the world’s largest milk producer.

Over the same period, per capita milk availability increased from 427 grams per person per day to 485 grams — a gain of about 13.6%. On the surface, this appears to confirm a familiar narrative: steady growth, rising availability, and a dairy sector continuing to deliver food security.

Yet the latest Basic Animal Husbandry Statistics (BAHS) 2025 data reveal a more layered reality. Production growth is not the same as access; national averages hide deep regional disparities, and India’s milk economy is becoming increasingly dependent on a handful of states and specific animal categories. The next phase of India’s dairy story will be defined less by volume expansion and more by distribution, productivity limits and sustainability.

A Growth Story That Is Beginning to Slow

Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, India added an average of 9–10 million tonnes of milk per year. Early in this period, annual growth rates hovered around 5–6%. More recently, they have eased to 3–4%.

This moderation is not accidental. It reflects:

- Rising feed and fodder costs

- Increasing water stress

- Labour shortages, especially in large milk-producing belts

- Signs of yield plateaus in crossbred cattle in some states

India is still growing its milk output, but at a more measured pace. The easy gains from herd expansion and basic productivity improvements are largely behind us.

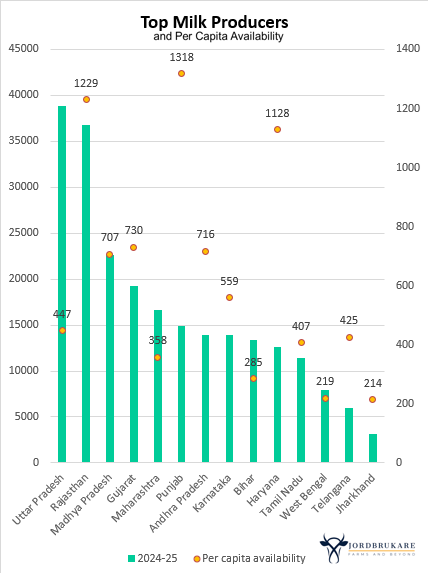

Five States Now Anchor India’s Milk Supply

Milk production in India is highly concentrated. In 2024–25, just five states accounted for over 54% of total national output:

Milk production in India is highly concentrated. In 2024–25, just five states accounted for over 54% of total national output:

- Uttar Pradesh: ~38.8 million tonnes

- Rajasthan: ~36.7 million tonnes

- Madhya Pradesh: ~22.6 million tonnes

- Gujarat: ~19.3 million tonnes

- Maharashtra: ~16.6 million tonnes

This concentration has important implications. North and western India dominate milk production, while eastern and north-eastern states contribute relatively little despite large populations.

As a result, national milk availability is structurally dependent on the performance of a small group of states. Weather shocks, fodder shortages, disease outbreaks or procurement disruptions in these regions can quickly translate into national price volatility and supply stress.

Per Capita Availability Is Rising — But Unevenly

Per capita milk availability rose to 485 g/day in 2024–25, up from 427 g/day in 2020–21. The increase is real, but it trails production growth because population growth absorbs a large share of incremental supply.

More importantly, per capita availability is not evenly distributed.

States such as Punjab (1,318 g/day), Rajasthan (1,229 g/day) and Haryana (1,128 g/day) enjoy some of the highest milk availability levels in the world. In contrast, several states and Union Territories remain far below the national average — sometimes dramatically so.

In Manipur, availability is about 41 g/day. In Lakshadweep, it is just 17 g/day. In Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, the figure is 4 g/day, according to statistics.

These disparities underline a critical point: India’s milk surplus is not evenly accessible. High-producing states export large volumes to urban centres and deficit regions, while local availability in some areas remains constrained by logistics, affordability and market access.

Cows Have Quietly Overtaken Buffaloes

One of the most important — and often overlooked — shifts in India’s dairy sector is the changing species mix.

By 2024–25:

- Cattle contributed about 53.5% of the total milk output

- Buffaloes accounted for about 43.1%

- Goats contributed roughly 3.3%

Within cattle, crossbred cows alone contribute nearly 31% of India’s total milk, making them the single largest source of milk nationally. Indigenous and non-descript cattle together add about 21%.

This shift reflects faster yield growth from crossbred cows, the expansion of organised procurement systems, and rising demand for liquid milk and value-added dairy products. Buffalo milk remains indispensable — particularly for high-fat products like paneer, khoa and ghee — but cattle milk is now the dominant force in volume terms.

Regional Dependence on Species Still Shapes the Market

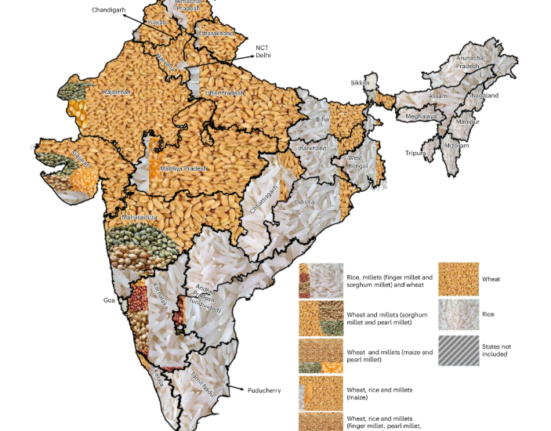

Despite the national shift toward cows, regional patterns remain pronounced.

- Buffalo milk dominates in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

- Cow milk dominates in the South, East and North-East, where buffalo populations are limited.

- Goat milk, though small nationally, is vital in island, hilly and arid regions. In Lakshadweep, nearly 88% of milk output comes from goats.

This diversity matters. Policy interventions on breeding, feed efficiency, emissions, or animal health will not have uniform effects across regions. India’s dairy future will require region-specific strategies rather than national templates.

What the Numbers Really Tell Us

Three conclusions stand out from the BAHS 2025 data:

First, India’s milk production growth is real, but it is increasingly concentrated geographically and biologically.

Second, rising output does not guarantee equitable access. National averages conceal deep regional and socio-economic divides.

Third, future gains will depend less on adding animals and more on productivity, quality, resilience and farmer profitability — especially in a context of climate stress and rising input costs.

Milk remains central to India’s nutrition, rural livelihoods and political economy. But the next phase of the dairy story will be shaped not by how much more milk India can produce, but by where it comes from, who can access it, and how sustainably it is produced.

The glass of milk on the table may look the same. The system behind it is changing — and the choices made now will determine whether India’s dairy growth remains inclusive, resilient and fit for the decades ahead.