The recently announced United States–Bangladesh trade arrangement has triggered renewed discussion across South Asia about the future of dairy trade flows. While the agreement is bilateral in structure, its implications extend beyond Dhaka and Washington — particularly for India, which sits at the centre of the region’s dairy economy.

From a Jordbrukare market intelligence perspective, the key question is not whether India will lose exports to Bangladesh overnight, but how evolving trade dynamics could reshape India’s role as a regional supplier — especially in commodities such as skim milk powder (SMP), butterfat, and select cheese categories.

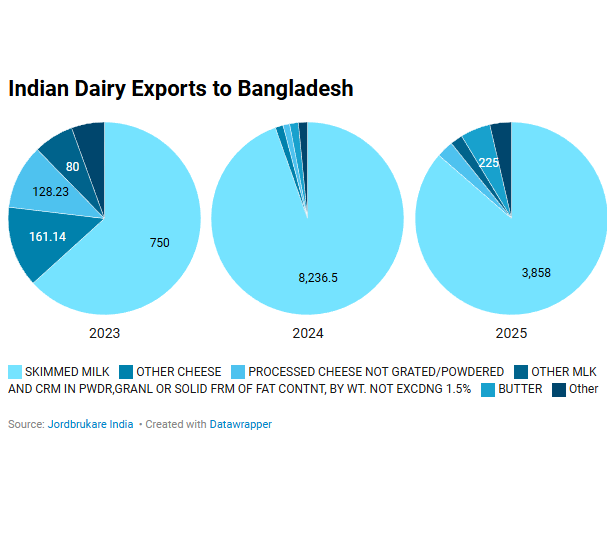

Using the latest Indian export data to Bangladesh (2023–2025), this note examines how trade patterns are evolving and what the emerging US presence could mean for India’s strategic positioning.

Bangladesh: A Nearby but Structurally Limited Market for India

Bangladesh remains a highly protected dairy market, with effective import protection often exceeding 50–60% for milk powders and significantly higher for fat products. Imports are typically used to stabilise domestic supply rather than as a permanent sourcing strategy.

For India, this has historically meant that exports occur in windows — when domestic shortages, price spikes, or policy adjustments create opportunities. Unlike New Zealand, which operates as a structural supplier globally, India’s engagement with Bangladesh has been tactical.

What the Data Says: India’s Export Profile Is Volatile

Skim Milk Powder — Large but Opportunistic

Indian exports of skim milk to Bangladesh show dramatic swings:

- 2023: 750 tonnes

- 2024: 8,236.5 tonnes

- 2025: 3,858 tonnes

The spike in 2024 suggests a temporary supply gap or favourable price arbitrage rather than sustained demand growth. Bangladesh appears to rely on imports selectively to balance its domestic market.

From an analytical standpoint, this confirms that India’s SMP exports are reactive — not anchored by long-term procurement contracts.

Butter — Gradual Expansion

Butter exports have grown steadily:

- 2023: 57.6 tonnes

- 2024: 128 tonnes

- 2025: 225 tonnes

This trend likely reflects growth in Bangladesh’s bakery and foodservice segments, which are expanding alongside urban consumption.

However, butter remains a globally traded commodity, meaning any change in tariff treatment or supplier competitiveness could influence future flows.

Cheese — Signs of Market Development

Mozzarella exports rose from zero to over 78 tonnes by 2025, while processed cheese volumes remain relatively stable.

This indicates a gradual shift in Bangladesh toward higher-value dairy consumption — particularly linked to quick-service restaurants and modern retail.

Yet India’s role here is still modest and vulnerable to competition from established global suppliers.

Ghee and Specialised Products — Cultural but Small

Exports of ghee remain minimal, reflecting niche demand rather than a commercial growth segment.

A Clear Pattern: India Acts as a Swing Supplier

Taken together, the data reveals a consistent pattern:

India supplies Bangladesh when conditions align — not as a primary source of dairy.

This “swing supplier” role is shaped by:

- Geographic proximity

- Flexible supply

- Policy windows

- Price competitiveness during surplus cycles

While advantageous in the short term, this position is inherently vulnerable to structural changes in trade policy.

Enter the US–Bangladesh Trade Deal

The new trade framework includes commitments by Bangladesh to open its market to US agricultural goods, including dairy, under phased tariff reductions. While effective protection remains high today, gradual liberalisation could lower the landed cost of US milk powders, butter, and other dairy ingredients.

For India, the significance lies less in immediate displacement and more in how import behaviour may evolve.

Where India Is Most Exposed

Skim Milk Powder

Given that SMP accounts for the bulk of India’s exports to Bangladesh, any increase in US competitiveness could reduce the frequency of large import spikes.

If Bangladesh secures more predictable access to global suppliers, reliance on opportunistic imports from India may decline.

Butterfat

Rising Indian butter exports could face stronger competition from US suppliers if tariff advantages emerge.

Cheese

India’s growing presence in mozzarella and processed cheese may encounter increased competition, particularly in industrial and foodservice channels.

Secondary Effects Through Global Markets

Trade dynamics rarely operate in isolation. If US suppliers gain share in Bangladesh, traditional exporters — particularly New Zealand — may redirect volumes elsewhere. This could intensify competition in markets where India is expanding, such as the Middle East.

Such indirect effects often matter more than bilateral trade shifts.

Strategic Interpretation for India

The data suggests that India’s challenge is not one of scale but of positioning. As regional markets gradually integrate into global supply networks, opportunistic exports may become less frequent.

India will need to consider whether to remain a reactive supplier or develop a more structured export strategy.

Strategic Considerations for Indian Stakeholders

- Strengthen cost competitiveness in milk powder production

- Build consistency and reliability in export supply chains

- Focus on differentiated products rather than commodity competition

- Monitor regional trade liberalisation trends closely

India’s comparative advantage lies in its vast production base and growing sophistication — but translating this into sustained export presence requires strategic intent.

What Jordbrukare Will Continue to Monitor

- Implementation of tariff changes under the US–Bangladesh framework

- Changes in Bangladesh import behaviour

- Price trends in milk powders and butterfat

- Policy signals from India regarding export strategy

- Competitive responses from global suppliers

Conclusion: A Subtle but Important Signal

India’s dairy exports to Bangladesh illustrate the realities of regional trade — proximity matters, but policy and global competition ultimately shape outcomes.

The emerging trade environment suggests that while India will remain a relevant supplier, its role may evolve. Moving from opportunistic participation toward strategic engagement will be key if India seeks to strengthen its position in South Asia’s changing dairy landscape.