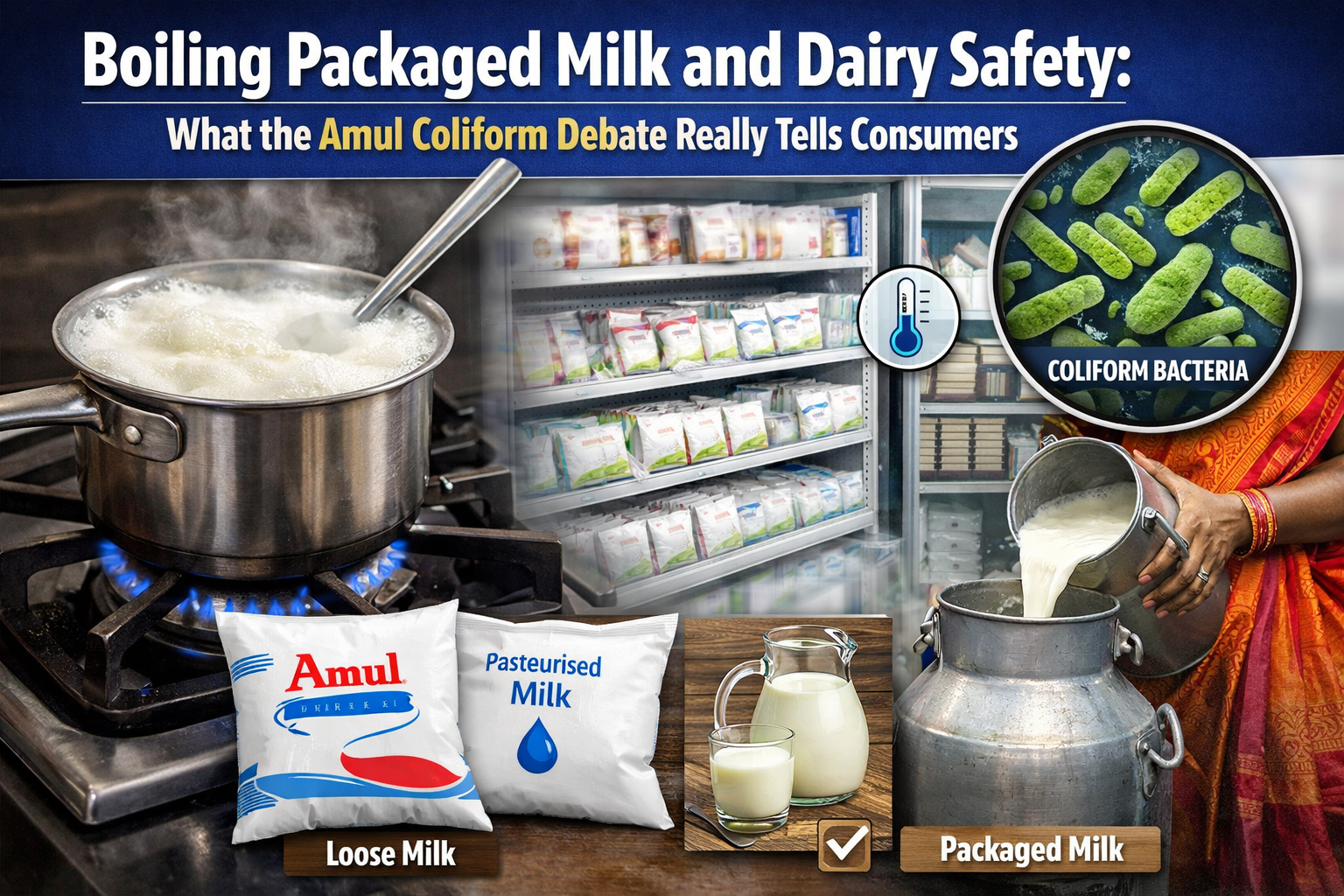

Milk seldom enters the public spotlight, yet recent reports alleging elevated coliform bacteria levels in packaged pouch milk, including products from Amul, have reignited consumer anxiety around dairy safety. While companies have denied manufacturing failures and regulators have intensified inspections, the episode has shifted attention to a more fundamental question: does boiling pasteurised milk for five minutes make it safe, and is loose milk a better alternative?

What Boiling Milk Actually Achieves

Packaged pouch milk sold in India is typically subjected to high-temperature short-time (HTST) pasteurisation, where milk is heated to approximately 72┬░C for 15 seconds and rapidly cooled. This process eliminates over 99 per cent of common pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella, but it does not render milk sterile.

When consumers boil milk at home and maintain a rolling boil for around five minutes, temperatures exceed 100┬░C. This secondary heat treatment destroys most remaining vegetative bacteria, including coliform organisms. From a microbiological standpoint, this significantly enhances safety and provides a critical second barrier against contamination.

However, boiling is not a cure-all. Heat does not neutralise chemical adulterants such as urea, detergents, caustic soda or synthetic additives. If present, these compounds remain unchanged and may continue to pose health risks despite prolonged boiling. In addition, excessive heating can reduce heat-sensitive nutrients, notably vitamin B12 and folate, marginally affecting nutritional quality.

Cold Chain Integrity Matters More Than Duration of Boiling

Pasteurised milk can become unsafe if the cold chain is compromised. Bacterial growth accelerates rapidly between 5┬░C and 60┬░C. Breakdowns during transportation, retail storage or doorstep delivery can allow microbial loads to rise before consumers ever apply heat.

This underlines why food safety experts recommend boiling pouch milk immediately after purchase and storing it below 4┬░C thereafter. Repeated heating and cooling cycles further increase contamination risk and should be avoided.

Ultra-high temperature (UHT) milk follows a different safety model. Heated above 135┬░C and aseptically packed, it remains shelf-stable until opened, explaining why it has featured less prominently in recent safety debates.

Packaged Milk Versus Loose Milk: A Risk Comparison

Loose milk retains cultural preference and perceived freshness, but it is unpasteurised. Raw milk can harbour pathogens such as Campylobacter, E. coli and Salmonella, with contamination risks rising if hygiene during milking and handling is inconsistent.

Packaged milk, by contrast, undergoes standardised pasteurisation, batch testing and sealed distribution, offering better protection against environmental contamination. From a food safety perspective, packaged milk remains the lower-risk option provided cold chain conditions are maintained.┬Ā Unless consumers have direct oversight of farm hygiene and handling practices, loose milk generally carries a higher microbiological risk.

Home Testing: Awareness, Not Assurance

Basic household tests can indicate certain forms of adulteration. Iodine drops may detect starch, foam persistence can suggest detergent presence, and surface flow tests can hint at dilution. Commercial home testing kits add another layer of awareness but cannot replace laboratory analysis.

The Takeaway

Boiling packaged milk for five minutes after the first rise significantly reduces bacterial risk but does not eliminate chemical adulterants. Cold chain integrity remains as critical as heat treatment.

For consumers, the safest approach is to purchase from reliable brands, boil promptly, refrigerate correctly and consider UHT milk for infants, the elderly and immunocompromised individuals. Milk safety debates benefit less from panic and more from scientific clarity. Informed handling, not brand switching alone, remains the strongest defence.